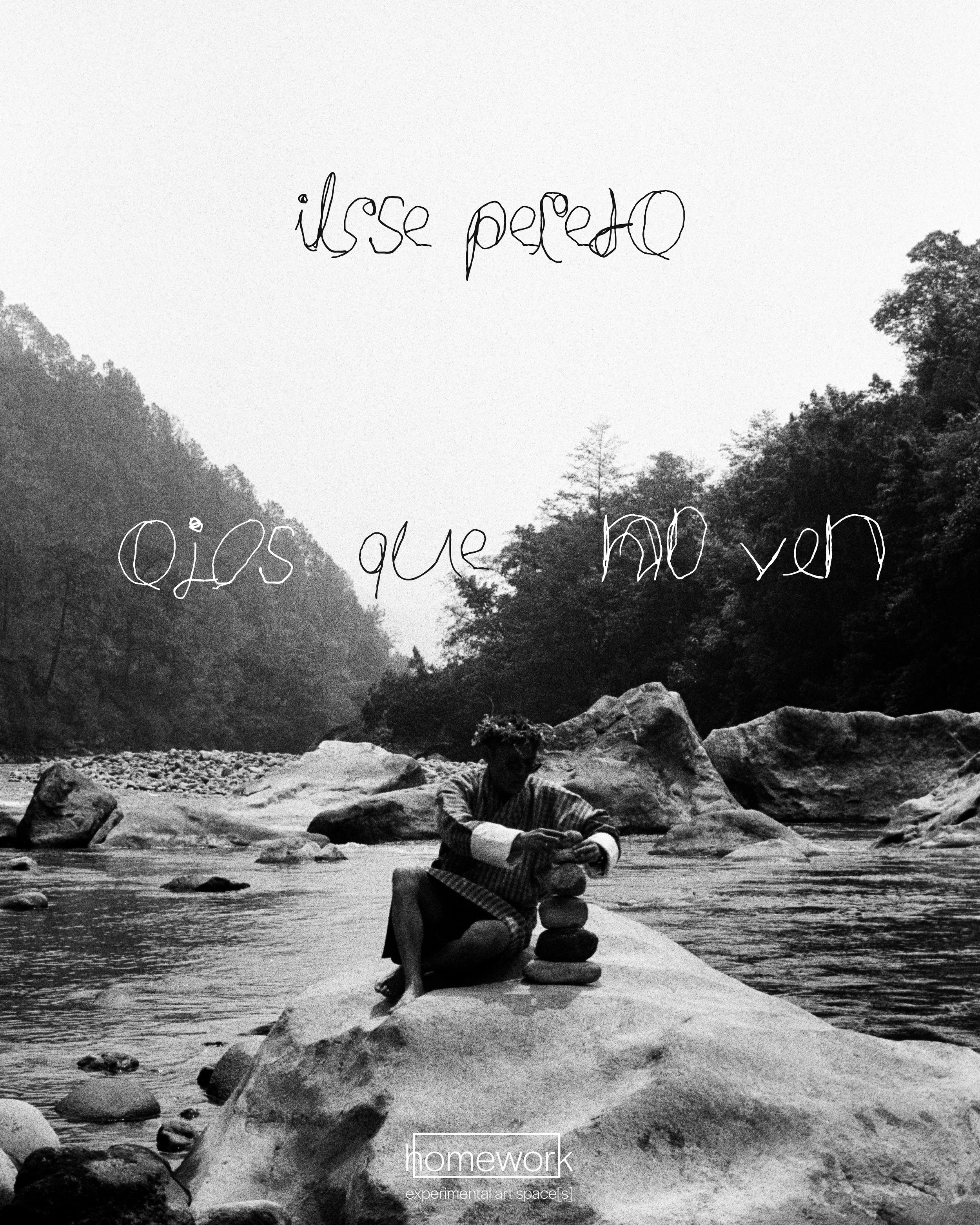

ojos que no ven

ilsse peredo

october 18 - december 13, 2025

7338 nw miami ct, miami fl

ilsse peredo’s solo exhibition 'ojos que no ven' stems from the proverb, "Ojos que no ven, corazón que no siente" (“out of sight, out of mind”). The phrase is intentionally left unfinished, inviting each viewer to complete it and to decide what happens when we choose not to look.

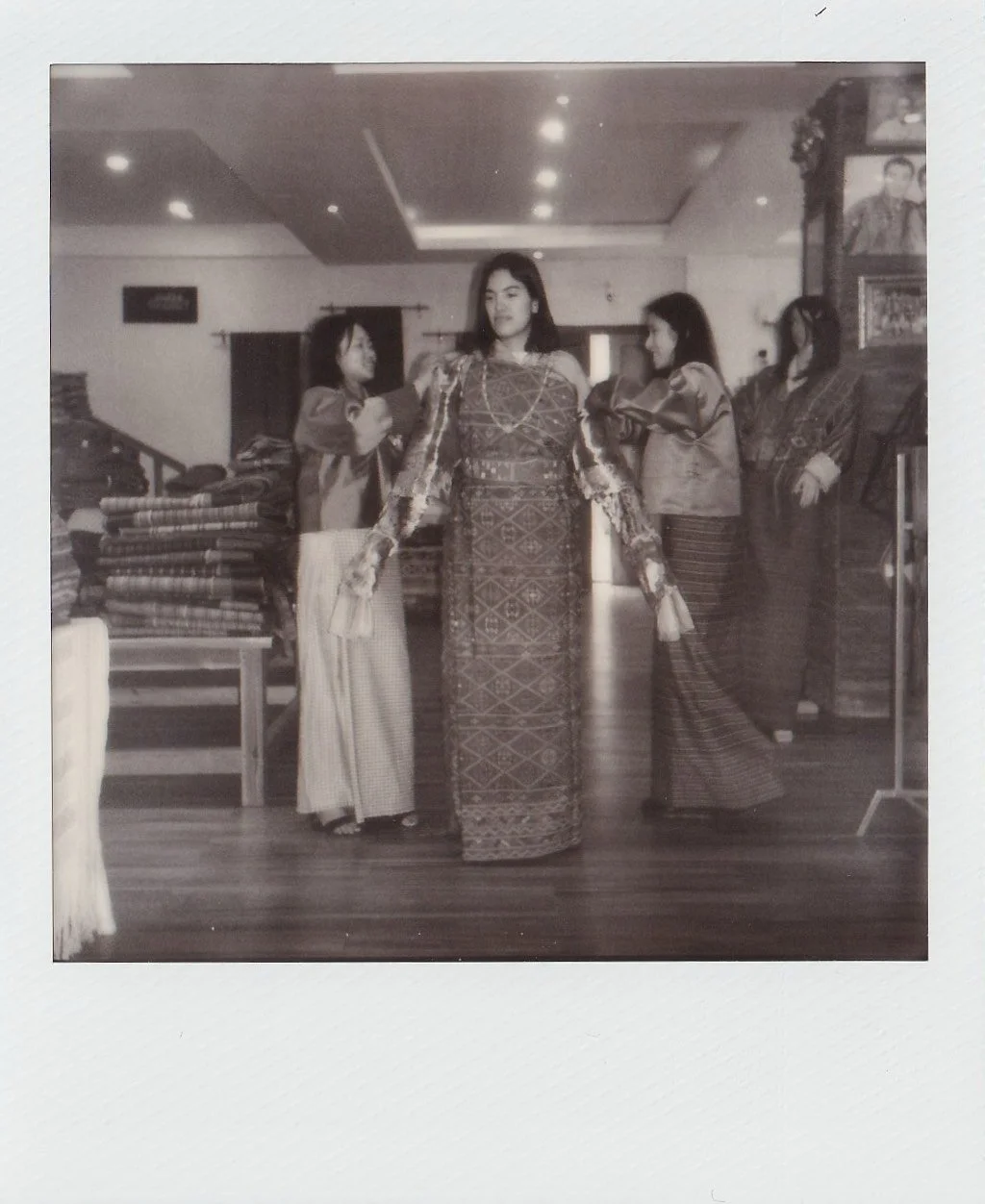

Inspired by Frida Kahlo’s question, “Feet, what do I need them for if I have wings to fly?” ‘ojos que no ven’ becomes a search for flight beyond familiar ground. Blending personal history with global concerns, this multi-sensory exhibition weaves together influences from recent pilgrimages the artist took through Mexico, Bhutan, and the Navajo Nation. Consequently, works in the show draw inspiration from Day of the Dead altars, Bhutanese prayer flags, and the Navajo principle of Hózhó.

While in Bhutan, peredo learned that happiness is not measured by money, as the country’s Gross National Happiness (alternate to GDP) places well‑being above economic growth. Along with learning that the truest prayers are the ones we say for others and that nature must be protected. In Mexico, she witnessed that to remember the dead is to give them another sunrise. That death is a passage, not an ending. In the Utah desert, she learned insights grounded in the Navajo concept of Hózhó, which embraces beauty, balance, and harmony. While accepting that gratitude leaves no room for fear and that desert landscapes embody lessons of impermanence and renewal.

Translucent photographic sculptures fill the room building on artistic lineages of expanded photography, particularly works that move beyond the flat image into three‑dimensional space. Aligning with Nicolas Bourriaud views on relational aesthetics, these unique photographic sculptures house spectral, ghostly images that invite visitors to move around and look through them as translucent portals while becoming part of the work themselves.

By dissolving the boundary between image and body, the artist proposes that empathy requires a physical and spiritual step across a threshold. Each image is charged with spirit and memory, while the central tri-cultural altar becomes a bridge between worlds, merging sacred objects and materials from three cultures and traditions.

‘ojos que no ven’ asks us to look closely and remember that empathy, reverence, and responsibility begin with how we see the world around us. Amid a global crisis of environmental degradation and social fragmentation, peredo draws on Mexican Catholicism, Indigenous Mesoamerican cosmologies, Bhutanese Buddhism, and Navajo teachings to challenge Western binary thinking. Her work envisions a world where diverse belief systems coexist, reminding us that to truly see is to remember our interconnectedness.

-curated by homework

artist

-

ilsse peredo, born in Mexico and based in Miami, is a multifaceted visual artist whose work moves across photography, video, performance, and immersive installations to explore the core of human experience. Her practice is a raw, unfiltered journey through a fragmented world, confronting viewers with their own stories and challenging them to find meaning in the chaos.

Her work unfolds in layers, questioning norms, breaking taboos, and rewriting dominant narratives. Each piece creates space for reflection, emotion, and engagement with truths often left unspoken. It’s an invitation to look deeper, confront assumptions, and reconnect with the shared threads of our humanity.

ilsse bridges the ancient and the contemporary, reimagining tradition in a modern context. She transforms the everyday into something sacred, urging us to recognize the beauty and complexity in what often goes unnoticed.

Her work has been shown at homework, Untitled Art Miami Beach, Feria Clandestina, Miami Art Society, Edge Zones, the Mexican Consulate in Miami, and other venues across the world.

A Letter from the Artist

This exhibition began as a quiet meditation on ego, empathy, and the pull of wonder. I have learned that ego builds walls, whispering that we exist apart. Empathy becomes the bridge, the act of stepping barefoot and unguarded into another life. And curiosity is the first spark. Without it I might never have left the familiar, never dared to enter another way of believing, another way of being.

Ojos que no ven is both a caution and an invitation. In Mexico we know the saying: Ojos que no ven, corazón que no siente—eyes that do not see, heart that does not feel. I leave the phrase unfinished so each visitor may decide how it ends. What happens when we choose blindness? What graces appear when we truly look?

I was born and raised in Mexico, a daughter of its earth and its saints, surrounded by the wisdom of mothers and abuelas. I grew up Catholic, breathing the language of prayer and ritual. I was taught that death is not an ending but a passage, that spirits remain close and must be honored with altars heavy with flowers, candles, and copal smoke. I learned that maíz is life itself, the body of our people, the seed that binds us to the soil. Family was sacred, memory a form of survival, food a ceremony, art a devotion. These teachings, sometimes contradictory and always luminous, became the foundation of my world.

As Frida Kahlo once asked, Pies, ¿para qué los quiero si tengo alas para volar? Why do I need feet when I have wings to fly? My parents gave me those wings. They trusted me with independence early, sending me to Rhode Island at thirteen. Later I lived in Switzerland, and eventually in Miami, which has now been my home for nearly eleven years. Along the way I have gathered blessings from many places, many faiths, many ways of living. My Mexican roots remain my heartbeat, but I am also made of the countless small pieces collected through journeys, friendships, lovers, teachers, elders. I am a chorus of voices and traditions, still forming myself, piece by piece.

For my twenty eighth birthday I offered myself my first true solo pilgrimage: Bhutan. The more I read, the more I knew I had to go. I spent fifteen days in a kingdom never colonized, where preservation is not nostalgia but resistance. Bhutan is the last remaining Buddhist kingdom, the land where Guru Rinpoche carried the teachings in the ninth century. It is a country where material wealth is light compared to spiritual abundance, where seventy percent of the land is protected forest and progress is measured in Gross National Happiness. Imagine a world where well being is measured by the health of our rivers and the strength of our communities.

Prayer is everywhere there. Valleys are strung with flags, blue for sky, white for air, red for fire, green for water, yellow for earth, each one releasing mantras to the wind. Nomads still tend their yaks on mountain slopes, carrying forward centuries of tradition. Monks and nuns give their lives to devotion. In spring, the Paro Tshechu fills the kingdom with sacred masked dances, tales of gods and demons, light triumphing over darkness. Even the phallus appears as a holy protector, painted on homes and worn as amulet, a blessing for fertility and joy.

On my last day I climbed to the Tiger’s Nest Monastery, four hours up and four hours down, carrying my cameras, the films I had exposed, prayer flags, paintings, even a carved wooden phallus I found in a small shop. At the summit a lama blessed me and every object I carried. Standing on the cliff’s edge, I prayed for clarity, for the shape of this exhibition. On the descent it came as a whisper: let them see through, let them stand inside the prayer. I knew then the photographs must be printed on translucent mesh, not as walls but as portals. When someone walks behind them, they become part of the image, part of the offering. The blessing belongs to anyone who steps inside.

Utah felt like entering the body of the earth itself. I walked on land that once lay beneath an ancient ocean, canyons carved by rivers into a vast archive of time. With Eli, my Diné guide, I slipped through three slot canyons. He told me the canyons breathe, that light is ceremony. He also shared a teaching that has stayed with me: when you are fully present and filled with gratitude, there is no room for any other thought. Gratitude, he said, is the purest form of prayer because it leaves no space for worry or fear. Standing in that red-gold silence, I felt the truth of his words. For the Navajo, the desert is alive and filled with spirit. To walk in Hózhó is to walk in beauty, to recognize the land as relative and ancestor.

Later, from a helicopter, I watched the Grand Canyon reveal layer after layer, some nearly two billion years old. From above, the river opened the earth like both wound and blessing. I felt small inside that immensity. I saw a turquoise river glowing against the red desert, and nearby Lake Powell stretched like a silent inland sea, mirroring the sky on its stone walls. The Navajo say these landscapes are teachers, and I believed them. They teach impermanence, erosion, renewal. They remind us that beauty is alignment, not ornament, and that we are not outside of nature but within it.

When I reached Izamal, the city of three cultures, I felt the layers of time before anyone explained them. Pyramids stand not as ruins but as neighbors. People wake each morning with these ancient temples outside their windows. The convent rises atop a pyramid, life flowing around both. The entire town is painted a deep, glowing yellow, as if the city itself were a constant offering to the sun.

My guide there, a man everyone called El Diablo with a conspiratorial grin, shared a teaching handed down from Maya elders: “Every dawn the sun is reborn because the people remember to greet it. If one day no heart offered greeting, the sky would forget to rise.” He said the first light is a covenant between humans and the cosmos, a reminder that our reverence keeps the world turning. His words settled over me like the hush before sunrise.

Kinich Kakmó, the great pyramid, is dedicated to the sun god who descends at noon in the form of a macaw. Alongside him the Maya honor Ixchel, goddess of the moon, fertility, and weaving. I sensed her in the lineage of women healers and midwives. Beneath the ground, cenotes opened like emerald eyes into the underworld, formed by the Chicxulub meteorite that ended the age of dinosaurs. For the Maya these waters were portals: offerings of jade, copal, ceramic vessels, even blood, were gifts for rain and renewal. People still say the cenotes are guarded by the Aluxes, playful spirits who demand respect from every visitor.

The Maya measured existence in cycles, harvests, seasons, births and deaths turning like stars. Yet Izamal also bears the scar of conquest: the convent of San Antonio de Padua built directly atop a pyramid once dedicated to the rain god. One temple layered upon another, yet not erased. Beneath the Virgin of Izamal, the old gods still breathe. You feel them both in the stones.

Oaxaca brought memory alive. It was not housed in museums but in mercados, kitchens, churches, and graveyards, carried forward in Zapotec and Mixtec tongues, in the weaving of huipiles, in the black sheen of barro negro pottery. I arrived for Día de Muertos, when the city becomes a threshold between worlds. Everywhere altars blazed with marigold light, copal smoke, mezcal, pan de muerto, and the photographs of the beloved dead. Graveyards shimmered like oceans of flame as music guided the spirits home. The scent of flowers—bitter and honeyed—marked the path for souls to return.

My guide Mario told me that every altar is a heartbeat of the earth. “When we remember,” he said, “we give the dead another sunrise, and we give ourselves another chance to live fully.” His words folded into the music and candlelight until the whole night felt like one continuous breath between worlds.

What moved me most was how strangers welcomed me. Families I had never met invited me to sit, to light candles, to share food and stories of their ancestors. They received me as their own as any good Mexican would and for a moment their memories became mine.

In Mexico, the altar is a doorway. Once each year our muertos return, and we prepare the way: petals like golden rivers to guide them, candles as beacons in the dark, copal smoke to cleanse, a glass of water for the long journey, pan de muerto and favorite dishes for nourishment, photographs and small belongings to call them home. Together these offerings form a map between worlds, a prayer made of scent, taste, and memory.

It was in Oaxaca that I first understood the altar not only as a passage for spirits but as a teacher for the living. The dead travel from el Mictlán; in Zapotec memory Mitla, Lyobaa, is the place of rest, the entrance to the underworld. That vision has never left me. The altar showed me that memory itself is devotion, and that to keep tradition alive is to keep the soul of a people alive.

At the center of this exhibition stands a tricultural altar built from what I carried back. From Bhutan: butter lamps, mantra paintings, incense, a sacred phallus, prayer flags, woven yak hair, cordyceps. From Utah: desert sand, stones, white sage, and dreamcatchers I made beside a Navajo woman who shared her knowledge. From Mexico: copal, ceramics, crystals, textiles.

As I arranged these pieces they began to speak to each other. Bhutan’s altars and Mexico’s altars mirrored one another, offerings of fire, scent, and memory. The desert sand and the cenote waters both hold extinction and rebirth. In Utah I stood where dinosaurs once swam; in Izamal I stood where they vanished. Even the colors connect: the yellow of Izamal’s walls, the gold of Bhutan’s temples, the sunlit stone of the Navajo desert, all vibrating with the same devotion. Different places, different languages, yet all reaching toward balance, toward the wholeness of the world.

Together these three worlds form a triad of knowledge: Bhutan as vision, Navajo as grounding, Mexico as memory. Their teachings meet here as portals, transparent images printed on mesh, suspended like banners, so that you see not only the photograph but also what lies beyond it. To walk through these works is to travel without leaving, to widen perception without crossing borders.

And in the end, that is what Ojos que no ven is for me: a return to seeing, to presence, to the boundless curiosity that has carried me through my life. Ego isolates and blinds; empathy invites us closer; curiosity opens the door. This exhibition is my way of opening that door so others might step inside and feel what is usually overlooked. If we dare to see, we may learn again how to feel.

Finally, a word on prayer. For me, prayer is the place where I lay down control. It is where I surrender the small self and place it in the care of the divine. It is where I remember that I do not have to force my way through life, that I can trust and be carried. My guide Karma in Bhutan taught me the way of prayer that has resonated most deeply with me. He told me never to pray for myself or for what I think I need. I should only pray for others—for the world, for peace, for Mother Earth. If I am ill, I should pray not for my own healing but for all who suffer the same pain.

And so I prayed: for young artists searching for a voice, for every woman traveling the world alone, for those who leave their homes and cross oceans in search of safety and dignity, for families exiled by conflict whose skies burn and borders harden, for those blinded by ego, for the forests and oceans and the creatures that keep us alive, for every heart aching to feel love again, for the quiet renewal of our planet. In those prayers I felt a freedom I had never known, a love large enough to hold the whole earth.

Prayer

Spirit who is river and flame

grant me the grace to quiet my ego

the faith to trust what I do not yet understand

the courage to step into mystery

and the wisdom to know that every culture, every voice, every prayer

reflects Your infinite face.

Guide us by the rhythms of earth and the guidance of Spirit

and let this blessing extend beyond me

so that all who enter may see, may feel, and may be carried by truth.

Amén · Sādhu · T’áá ákót’ée doo

— ilsse peredo

Miami, 2025

activations

-

ilsse peredo's 'ojos que no ven' - opening reception

October 18th at 5pm

-

homework in conversation

Artist ilsse peredo in conversation with Aurelio Aguiló and Mayra Mejía of homework.

Centered on peredo’s new exhibition, “ojos que no ven,” the discussion will expand into an exploration of her broader artistic practice, conceptual motivations, and the personal and cultural frameworks that inform her work.

Together, they examine the show’s themes of invisibility, memory, and resistance, as well as the contexts—social, spatial, and psychological—that shape her approach to artmaking.

-

'ojos que no ven' visual essay launch

The launch of ilsse peredo’s limited edition visual essay ‘ojos que no ven’ at homework.

Limited edition copies of the book available for purchase.

The evening featured a intimate vinyl set by Jesús Rodríguez of Rum & Coke, and a special michelada bar.

Featuring works from ilsse’s current exhibition and beyond, the book also includes a personal letter from the artist, mapping the emotional and visual threads that connect Bhutan, Utah, Izamal, and Oaxaca.

-

‘corazon que no siente’ - special performance directed by ilsse peredo

Saturday, November 29 from 5:30pm-8:00pm

Centered on body and movement, the performance featuring 2 dancers explores connection and perception all within her current immersive exhibition which is titled ‘ojos que no ven.’

-

Little Haiti Little River Art Day/Closing of 'ojos que no ven'

HIGHLIGHTING ARTS AND CULTURE IN LITTLE HAITI AND LITTLE RIVER